The limited size of this book does not allow any substantial commentaryon the Crusades except to mention some facts that influenced, in one way or another, the development of Western European Christian art. The cultural exchange between two Abrahamic religions – Islam and Christianity – happened in more or less peaceful conditions on the background of the Byzantine Empire, Spain and the Kingdom of Sicily, while the non-stop slaughter of the Crusades wasn’t very culturally beneficial. Nevertheless, the Crusades caused one really important development in the life of Western Europe, including its art – the emergence of military monastic orders, two of which rose to early prominence: the Order of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem (Order of the Hospitallers), founded in 1113; and the Order of the Temple, founded in 1119. While the Order of Hospitallers initially was a medical order, later it began to guard pilgrims and give them refuge in so-called hospitals in the desert. Meanwhile, the Order of the Temple, from the very beginning, was created by Hugo Debyn as an order of military ascetics carrying Christianity at the tip of their swords, and that was essentially a new development in Civilization Christianity, turning its theology into a military science.

This military science was connected with the Cistercian reform and this can be derived from no more than the fact that the authors of the first rule of the Order of the Temple, which later on became a template for all the later rules of military ascetic societies in the West, were Hugo Debyn and Bernard of Clairvaux. But the real birthday of the Order of the Temple wasn’t the time when the order was founded by Hugo Debyn, but rather March 29, 1139, the date Pope Innocent II issued his bull, “Omni Datum Optimum,” which was later called the “Great Charter of the Liberties of the Templar Knights.” He signed this “Magna Carta” of the Templars in celebration of the downfall of his competitor antipope Anicletus II. In this bull, Innocent II thanked the followers of St. Bernard of Clairvaux for their help in defeating “a man of Jewish origin who occupied the throne of St. Peter.” This unprecedented documents gave to the Order of the Temple a large number of extremely unusual privileges, for instance, the right to cross all borders freely (meaning without taxes), the freedom not to pay the tenth part from their income to the Church and the right not to be obedient to any Church authorities except the Pope himself. It gave to the Order of the Temple a new quality, turning it into not only a military organization, but the first supranational corporation, which brings to mind the Comintern or the International Monetary Fund. Taking advantage of these liberties, the Templar knights appeared to be the first ones to transfer money with the help of checks, thus becoming the first transnational corporation and the inventors of financial capitalism. But the most important privilege granted to the Order of the Temple by Pope Innocent II appeared to be the right and even duty of the Templar Knights to do business with heretics, criminals and those who were expelled from the Church, for the sake of saving their souls. The profitability of this privilege was determined by the fact that at that time, while the followers of the Abrahamic religions – Christians and Muslims – were fighting with each other in the Middle East non-Abrahamic religions, one of which was the Cathars – or as they were called in Languedoc, Albigensians – appeared and started to spread rapidly in Western Europe.

The religious philosophy of the Cathars was a synthesis of a large number of gnostic sects as well as Roman Catholic heretics. But the most important circumstance was that the appearance of these sects and their expedient growth was determined by the unique cultural agar agar created by the victory of Civilization Christianity in Western Europe. The visible symbol of this victory was the defeat of St. Bernard of Clairvaux over the Antipope Anicletus II in spite of the fact that this victory appeared to be Pyrrhic. Indeed, several years after the death of Anicletus II, the secular power of the Popes over Rome was overthrown, and in 1143 the City of Rome became a republic managed by the former students of Peter Abelard, Arnold of Brescia, and Jordan di Perlione, the brother of Anicletus II. To make things even more confusing, another student of Peter Abelard, Guido DiCastello, was elected Roman pope Celestine II after the death of Innocent II.

In England, the situation appeared to be even more complicated as the Papacy was self-defeated there, trying to make their victory more than complete, thus revealing the universal meaning of the saying, “better is the worst enemy of good.” After Archbishop of Arno St. Malachi imposed the Roman Catholic rite on the Irish Church, the Cistercians managed to shoot themselves in the foot deciding to celebrate the elimination of Celtic Orthodox Christianity by forcing the archbishopric of York to accept as its head the Cistercian monk, Henry Merdack. Considering that the archbishopric of York traditionally was granted the right to elect its own head, and already had exercised this liberty by electing William Fitz-Herbert, who was supported by King Stefan of England, such a denial of the traditional liberties of York fanned the flame of conflict between the Anglo-Norman monarchy and the Catholic Church. In spite of, or maybe due to, the fact that the Roman Catholic Church supported the conquest of England by William I (the Bastard), this conflict survived even the death of Cistercian Pope Eugenius III, Bernard of Clairvaux and Henry Merdack, who all died one after the other within a month in 1153. Meanwhile, William Fitz-Herbert, who had come to Rome to be confirmed as Archbishop of York, was forced to flee to the court of Roger II of Sicily to avoid being murdered by Cistercians, but after the death of Pope Eugenius III, the new Pope, Anastasy IV, confirmed his election as Archbishop of York, and he returned there to take charge of his see. But upon his arrival there, he was poisoned, and the poison was found in the chalice he used at liturgy. This event definitely didn’t cause the fire of the conflict between the Anglo Norman monarchy and the Catholic Church to subside, and this flame still burns, sometimes becoming brighter in order to highlight the unbelievable beauty of Anne Boleyn or the talents of a seaman, St. Francis Drake. But the real catastrophe for the Cistercian order happened when, a few months after his death, the burial place of William of York, located in the York cathedral became famous as a place of miraculous healing and a source of other miracles, thus making the moral authority of Cistercians, which had been fairly high due to the efforts of St. Bernard of Claivaux, diminish not only in England but in all of Western Europe.

This moral fall of the Cistercians turned their favorite child, the Order of the Temple, into muscle without brains, and in this world, no power can stay without somebody taking over. The Albigensians, who called themselves the Good Christians, but who were then very much afraid of St. Bernard’s attention, and later on of similar attentions of St. Dominic, began to join the Order of the Temple, taking advantage of the “Magna Carta” of the Templar Knights. This process was mutually beneficial, especially if one takes into account that the “Good Christians” from Albi were transferring their property to the Order of the Temple and their behavior superficially fit perfectly with the ascetic ideal drawn by St. Bernard of Clairvaux. In a situation when the cultures of Western Christianity were turned into cultural agar-agar by the victory of Political Christianity, the Albigensians enriched the Order of the Temple not only by their material possessions, but also by their gnostic knowledge. In Languedoc and Provence the commandories of the Templars were prosperous from the moment that the Order was founded and were quite numerous not only because of the proximity of Saracens but rather because of the widespread presence of Albigensians, who very often used these commandories to escape the threats of the followers of St. Bernard and St. Dominic. Indeed, members of the Order of the Temple were the only ones who were given the right by the Pope to take care of the souls of heretics without any damage to their physical wellbeing. That caused the cultural exchange between the Templars and the Albigensians to be extremely fruitful, thus contributing to the appearance of the most amazing culture of Languedoc.

The songs of the troubadours of Languedoc tell more about the Albigensians and their worldview than the protocols of the Inquisition. In the heart of this culture and the Languedocian poetry was courtly or platonic love to a Fair Lady. This calls to mind not only Plato but also the Platonic academy in Athens and indeed, the Albigensians were the ideological descendants not only of the Platonic academy, which had been disbanded by Emperor Justinian, but also of the Syrian gnostics mentioned in Holy Scripture (Rev. 2:6), and the unsuccessful recruiters of St. Augustine, the Manicheans. The Albigensians were very variable in their religious philosophy, but their common point, their characteristic feature, was the fact that in one way or another they built their Gnostic and dualistic theories on a Manichean interpretation of Christian literature. They inherited from their ideological parents the association of matter with ¬ at minimum – godlessness, if not full-on evil and all their myths and theories basically agreed that the God of the Old Testament, Yahweh, was essentially different from Christ, and was actually none other than Rex Mundi – the demiurge of this world and creator of matter, who was responsible for all the failures of this world and the consequent suffering of people in it. According to their philosophy, Christ was a denial of the God of the Old Testament and was rather a Paraclete who came into this world as a prophet and a teacher, reminiscent of the Good Shepherd of the Arians. To Albigensians his goodness was a derivative of his being the creator of another world – the world of spirit – immaterial and thus free from flaws.

The communal life led by the Albigensians was proclaimed to be the life of the early Christians, assuming that it was perfect, but actually it was quite different and rather was reminiscent of the contemporary Catholic church. For instance, they subdivided themselves into clergy and layman that they called perfecti and profane. Upon joining the Albigensian church, the profane (sometimes called credenti, or the “believers”) were not required to change their lifestyle, but they were obligated to admit the spiritual guidance of the teachers or perfecti (the “perfect”), who were both clergy and monastics. A perfecti could be a man or a woman, but they were all obligated to follow asceticism and had to go through a certain mysteria that was called consolamentum, a rite performed by the Albigensian bishop by the laying on of hands, which introduced the spirit of the Paraclete into the new perfecti. It is also important to mention that the word Paraclete in Albigensian terminology came not from the Christian “Comforter,” but rather from the self-given title of Mani, the founder of the Manichean religion. As history showed, the success of this anti-Abrahamic religious philosophy, or rather, worldview was determined by its complementarity to Civilization Christianity, which became especially important after the victory of the Cisterians in Western Europe. The Albigensian religious philosophy helped to release the creative potencies of man being held in the concrete prison of the Puritanism established by the Cistercian reform. The troubadours of the Languedoc, under the influence of the Albigensians, managed to provide expressive forms for the poetic and symbolic imagination of Western European Christians, unifying Christian symbolism with Celtic, Norman and German myths. The result of this synthesis first appeared in Languedoc, but later on became famous as a British myth and as such today appears to be the most important way of interpreting reality in the modern world. The corresponding parts of this synthesis are imprinted in the mentality of Western Christians and consist of the following myths:

4. The alternative myth to the “mystery birth”, also connected with the legend of “The Holy Grail”, is the legend of the “King under the Hill” or the True King of Britain, which has to do with the immortality of King Arthur. According to this legend, Arthur is a true monarch who didn’t die in the battle with Mordred, but was healed by the fairies of the Island of Abalone (Avalon), where he is waiting in sleep even now for the day when he will wake up and save Britain from a grave danger, thereby restoring the true monarchy of Britain. According to the legend, the entrance to the island of Avalon, inaccessible to regular mortals, is on the Hill of St. Michael, also known as the Glastonbury Tor, in the middle of the ruins of the Church of St. Michael.

It is very interesting that the legend of Joseph of Arimathea, as well as the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, became the national myth of the English in spite of the fact that the first legend was articulated by the French poet Robert de Boron in his book Joseph d’Arimathe, while the second legend was presented by the troubadour of Aquitaine, Chrétien de Troyes, in his book Merlin. It is also interesting that King Arthur, who became an archetypal hero of Anglo-Saxon civilization, was a military leader of the Christian Celts who imposed a crushing defeat on the pagan Saxons. This alone shows that the English as a nation considered their Christianity to be above ethnicity and that the 13th century conflict between the English and the French, known as the Hundred Years War, was rather a cultural and religious war. One shouldn’t overlook the fact that this conflict in the 13th century was a direct consequence of the Albigensian Crusade in the 12th century, as the subjects of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine became one people by culture and by sovereignty immediately prior to this tragic event. Considering that the military and economic might of the two vassals of the French crown, Languedoc and England, exceeded the might of the rest of France, the Capetian dynasty definitely felt itself to be in grave danger. This conflict was transformed into a culture war as after England and Langedoc were joined by the marriage of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine they began to develop a joined new culture that was quite different from the Gothic culture created by Abbot Suger [Unfortunately, when this culture war became intertwined with Papal ambitions and with the ethnic conflict between the Franks and the Gallo-Roman population of Occitaine, it turned into the genocide of the Albigensian Crusade, making the cruelties and devastation of the Hundred Years War its inevitable consequence.

To make things even more complicated, the Albigensian Crusade started the clock ticking on the time bomb of another conflict. First of all, it is important to mention that the Order of the Temple was a second church inside the Church, the first one being the College of Cardinals. No wonder that even the small number of Albigensians, joining the Order of the Temple made the College of Cardinals nervous, but when the Albigensians, very critical about recently created hierarchy of the Papacy, began to become members of the ruling hierarchy of this alternative church inside the Church, this nervousness turned into madness. It is very well-known that having a common enemy is the best reason for friendship, and when the Cardinals found out that French King Philip the Fair was deeply in debt to the Order of the Temple, the strategic union of the College of Cardinals with the Capetian dynasty made the Albigensians and Templars the inevitable victims of the same enemy. When the Albigensian Crusade started, joining the Temple Order became almost the only way for the Cathar nobility to avoid an absolutely degrading and painful death at the hands of the Crusaders of Simon de Montfort. This caused the Order of the Temple to become a poetic society of heavily armed troubadours and minstrels, plus making the preceptories of the Order very prosperous, as the Albigensians who joined the Order of the Temple transferred their property to it. This is particularly important because the Albigensians, who initially considered being perfecti or profane to be independent from the estate of their members, after joining the Order became particularly attentive to the difference between knights of noble origin and commoners, who at most would become surgeons and squires of the Order. The synthesis of these quite different world views solidified the subdivision of people into perfecti as people of spirit, sometimes called pneumatics, and people of matter, called profane, so that this subdivision was determined only by genetics, not by the behavior of a man or even by his personal abilities. Perfecti could be ascetics or occupy themselves with absolutely disgusting orgies, but they still remained people of spirit and humans of the higher order with respect to the profane, who were commoners and of lower estate by birth and whose right to exist was determined by their usefulness to the perfecti. The particular sign of being a perfecti was a refusal to participate in sexual procreation, which meant not the absence of physical contact with the opposite sex, but rather a refusal to create a family and give birth to children. A famous Russian movie, “The Night Guard” by Beckmambatov, almost perfectly illustrates the synthesized culture of the Templars and the Albigensians, particularly that the people of light and the people of darkness in this movie both appear to be perfecti and are in constant dynamic equilibrium with each other, while the commoners exist only as a faceless mass in the background. The group sex and other sexual perversions were considered by these descendants of the Manicheans to be a sign of being a perfecti, and the lowest level was occupied by peasants, as plants also procreate through sexual relationship, and this attitude appears to be which is in perfect harmony with the customs of the Manicheans as they were described by St. Augustine and St. Ambrosius. This cross-century philosophical continuity is both amazing and important, especially considering that these saints were among the very few apologists of Christianity who managed to convert a large number of gnostic-dualists.

Later, during the Second Crusade, the Templar knights enriched their political and religious experience by a cultural exchange with the followers of Hassan-i- Sabbah, who was the first to understand that a secret service having at its disposal fanatic murderers and terrorists, whose deadly power directed against the leaders of the enemy is much more effective than a regular army, and that sex and hashish can overcome the fear of death and supply to this secret service an unlimited amount of such fanatics. But even more important to the Templars was the discovery that the followers of Hassan-i-Sabbah were trying to achieve universal power not for its own sake, but rather as a tool, while their real goal was to create an almost scientific school of gnosis in the Castle of Alamut, which means “an Eagle’s Place.”

Meanwhile, world history was coming to a point of bifurcation that would drastically change the direction of the development of humanity. Most of the time people and civilizations develop along a certain road or a paradigm of development when one event appears to be a direct consequence of the other. This does not exclude the will of man to change the course of history and to leave this road, but it would take the enormous effort and gigantic willpower of someone like Alexander the Great or Confucius to change the flow of history just to demonstrate that the way back to the road after their death is inevitable. But sometimes humanity comes to a point of bifurcation when this road disappears and the butterfly effect becomes real, so that very small events can cause quite a substantial change in the paradigm of development, eliminating enormous civilizations while at the same time creating new ones. From that point of view it is very interesting that in 1956 a man whose name was Pierre Plantar registered a nonprofit organization under name the “Priory of Zion,” and later suggested to Europeans that they should consider reestablishing the monarchy of the Merovingians in Europe. In order to justify such a drastic political change, he identified as a point of bifurcation the year 1118, when the so-called “cutting down of an elm” took place. According to Plantar’s interpretation of history, this event caused the schism between the Priory of Zion and its military administrative instrument, the Order of the Temple, thus changing the flow of history and causing “Destruction of Europe” that we observe today. I don’t want to deny the importance of Merovingians for the unification of Western Europe, nor do I want to deny the reality of the 1000 years’ history of the Priory of Zion, however, from my point of view, the cutting down of an elm that stood on the border between Normandy and France and was a traditional place of negotiations for Norman dukes and French Kings, more than anything else meant the denunciation of the Treaty of St. Claire sur-Epte between Rollo and Charles the Simple, which made Normans the driving force of Western European civilization and for 300 years had been pulling Western Europe out of the state of barbarism and became one of the most important factors in the Christianization of Europe, including Scandinavia and Kievan Rus. Just 40 years after that the world drastically changed and the political map started to look like the one we see today.

© Alexander Brodsky

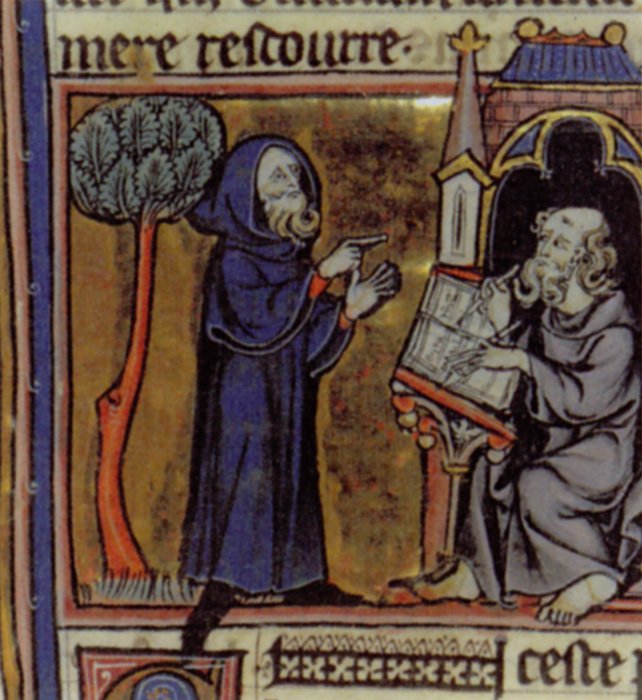

"Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem, grants the ownership of the location of the Temple of Solomon to Hugho de Payn and Gaudefroy St. Homer. Illumination in "History of overseas" of William of Tyre, XIII c, Bibliotheque nationale de France. |  The original headquarters of the Knights Templar, now Al-Aqsa mosque on the Temple Mount. Knights Templars believed this mosque to be the Temple of Solomon, hence the name of Templar. |

The religious philosophy of the Cathars was a synthesis of a large number of gnostic sects as well as Roman Catholic heretics. But the most important circumstance was that the appearance of these sects and their expedient growth was determined by the unique cultural agar agar created by the victory of Civilization Christianity in Western Europe. The visible symbol of this victory was the defeat of St. Bernard of Clairvaux over the Antipope Anicletus II in spite of the fact that this victory appeared to be Pyrrhic. Indeed, several years after the death of Anicletus II, the secular power of the Popes over Rome was overthrown, and in 1143 the City of Rome became a republic managed by the former students of Peter Abelard, Arnold of Brescia, and Jordan di Perlione, the brother of Anicletus II. To make things even more confusing, another student of Peter Abelard, Guido DiCastello, was elected Roman pope Celestine II after the death of Innocent II.

In England, the situation appeared to be even more complicated as the Papacy was self-defeated there, trying to make their victory more than complete, thus revealing the universal meaning of the saying, “better is the worst enemy of good.” After Archbishop of Arno St. Malachi imposed the Roman Catholic rite on the Irish Church, the Cistercians managed to shoot themselves in the foot deciding to celebrate the elimination of Celtic Orthodox Christianity by forcing the archbishopric of York to accept as its head the Cistercian monk, Henry Merdack. Considering that the archbishopric of York traditionally was granted the right to elect its own head, and already had exercised this liberty by electing William Fitz-Herbert, who was supported by King Stefan of England, such a denial of the traditional liberties of York fanned the flame of conflict between the Anglo-Norman monarchy and the Catholic Church. In spite of, or maybe due to, the fact that the Roman Catholic Church supported the conquest of England by William I (the Bastard), this conflict survived even the death of Cistercian Pope Eugenius III, Bernard of Clairvaux and Henry Merdack, who all died one after the other within a month in 1153. Meanwhile, William Fitz-Herbert, who had come to Rome to be confirmed as Archbishop of York, was forced to flee to the court of Roger II of Sicily to avoid being murdered by Cistercians, but after the death of Pope Eugenius III, the new Pope, Anastasy IV, confirmed his election as Archbishop of York, and he returned there to take charge of his see. But upon his arrival there, he was poisoned, and the poison was found in the chalice he used at liturgy. This event definitely didn’t cause the fire of the conflict between the Anglo Norman monarchy and the Catholic Church to subside, and this flame still burns, sometimes becoming brighter in order to highlight the unbelievable beauty of Anne Boleyn or the talents of a seaman, St. Francis Drake. But the real catastrophe for the Cistercian order happened when, a few months after his death, the burial place of William of York, located in the York cathedral became famous as a place of miraculous healing and a source of other miracles, thus making the moral authority of Cistercians, which had been fairly high due to the efforts of St. Bernard of Claivaux, diminish not only in England but in all of Western Europe.

Рукоположение архиепископа Святого Вильяма Йоркского. Витражи Йоркского собора |  Чудо исцеления у гробницы Святого Вильямв Йоркского. | Йоркский собор |

The songs of the troubadours of Languedoc tell more about the Albigensians and their worldview than the protocols of the Inquisition. In the heart of this culture and the Languedocian poetry was courtly or platonic love to a Fair Lady. This calls to mind not only Plato but also the Platonic academy in Athens and indeed, the Albigensians were the ideological descendants not only of the Platonic academy, which had been disbanded by Emperor Justinian, but also of the Syrian gnostics mentioned in Holy Scripture (Rev. 2:6), and the unsuccessful recruiters of St. Augustine, the Manicheans. The Albigensians were very variable in their religious philosophy, but their common point, their characteristic feature, was the fact that in one way or another they built their Gnostic and dualistic theories on a Manichean interpretation of Christian literature. They inherited from their ideological parents the association of matter with ¬ at minimum – godlessness, if not full-on evil and all their myths and theories basically agreed that the God of the Old Testament, Yahweh, was essentially different from Christ, and was actually none other than Rex Mundi – the demiurge of this world and creator of matter, who was responsible for all the failures of this world and the consequent suffering of people in it. According to their philosophy, Christ was a denial of the God of the Old Testament and was rather a Paraclete who came into this world as a prophet and a teacher, reminiscent of the Good Shepherd of the Arians. To Albigensians his goodness was a derivative of his being the creator of another world – the world of spirit – immaterial and thus free from flaws.

The communal life led by the Albigensians was proclaimed to be the life of the early Christians, assuming that it was perfect, but actually it was quite different and rather was reminiscent of the contemporary Catholic church. For instance, they subdivided themselves into clergy and layman that they called perfecti and profane. Upon joining the Albigensian church, the profane (sometimes called credenti, or the “believers”) were not required to change their lifestyle, but they were obligated to admit the spiritual guidance of the teachers or perfecti (the “perfect”), who were both clergy and monastics. A perfecti could be a man or a woman, but they were all obligated to follow asceticism and had to go through a certain mysteria that was called consolamentum, a rite performed by the Albigensian bishop by the laying on of hands, which introduced the spirit of the Paraclete into the new perfecti. It is also important to mention that the word Paraclete in Albigensian terminology came not from the Christian “Comforter,” but rather from the self-given title of Mani, the founder of the Manichean religion. As history showed, the success of this anti-Abrahamic religious philosophy, or rather, worldview was determined by its complementarity to Civilization Christianity, which became especially important after the victory of the Cisterians in Western Europe. The Albigensian religious philosophy helped to release the creative potencies of man being held in the concrete prison of the Puritanism established by the Cistercian reform. The troubadours of the Languedoc, under the influence of the Albigensians, managed to provide expressive forms for the poetic and symbolic imagination of Western European Christians, unifying Christian symbolism with Celtic, Norman and German myths. The result of this synthesis first appeared in Languedoc, but later on became famous as a British myth and as such today appears to be the most important way of interpreting reality in the modern world. The corresponding parts of this synthesis are imprinted in the mentality of Western Christians and consist of the following myths:

4. The alternative myth to the “mystery birth”, also connected with the legend of “The Holy Grail”, is the legend of the “King under the Hill” or the True King of Britain, which has to do with the immortality of King Arthur. According to this legend, Arthur is a true monarch who didn’t die in the battle with Mordred, but was healed by the fairies of the Island of Abalone (Avalon), where he is waiting in sleep even now for the day when he will wake up and save Britain from a grave danger, thereby restoring the true monarchy of Britain. According to the legend, the entrance to the island of Avalon, inaccessible to regular mortals, is on the Hill of St. Michael, also known as the Glastonbury Tor, in the middle of the ruins of the Church of St. Michael.

It is very interesting that the legend of Joseph of Arimathea, as well as the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, became the national myth of the English in spite of the fact that the first legend was articulated by the French poet Robert de Boron in his book Joseph d’Arimathe, while the second legend was presented by the troubadour of Aquitaine, Chrétien de Troyes, in his book Merlin. It is also interesting that King Arthur, who became an archetypal hero of Anglo-Saxon civilization, was a military leader of the Christian Celts who imposed a crushing defeat on the pagan Saxons. This alone shows that the English as a nation considered their Christianity to be above ethnicity and that the 13th century conflict between the English and the French, known as the Hundred Years War, was rather a cultural and religious war. One shouldn’t overlook the fact that this conflict in the 13th century was a direct consequence of the Albigensian Crusade in the 12th century, as the subjects of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine became one people by culture and by sovereignty immediately prior to this tragic event. Considering that the military and economic might of the two vassals of the French crown, Languedoc and England, exceeded the might of the rest of France, the Capetian dynasty definitely felt itself to be in grave danger. This conflict was transformed into a culture war as after England and Langedoc were joined by the marriage of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine they began to develop a joined new culture that was quite different from the Gothic culture created by Abbot Suger [Unfortunately, when this culture war became intertwined with Papal ambitions and with the ethnic conflict between the Franks and the Gallo-Roman population of Occitaine, it turned into the genocide of the Albigensian Crusade, making the cruelties and devastation of the Hundred Years War its inevitable consequence.

To make things even more complicated, the Albigensian Crusade started the clock ticking on the time bomb of another conflict. First of all, it is important to mention that the Order of the Temple was a second church inside the Church, the first one being the College of Cardinals. No wonder that even the small number of Albigensians, joining the Order of the Temple made the College of Cardinals nervous, but when the Albigensians, very critical about recently created hierarchy of the Papacy, began to become members of the ruling hierarchy of this alternative church inside the Church, this nervousness turned into madness. It is very well-known that having a common enemy is the best reason for friendship, and when the Cardinals found out that French King Philip the Fair was deeply in debt to the Order of the Temple, the strategic union of the College of Cardinals with the Capetian dynasty made the Albigensians and Templars the inevitable victims of the same enemy. When the Albigensian Crusade started, joining the Temple Order became almost the only way for the Cathar nobility to avoid an absolutely degrading and painful death at the hands of the Crusaders of Simon de Montfort. This caused the Order of the Temple to become a poetic society of heavily armed troubadours and minstrels, plus making the preceptories of the Order very prosperous, as the Albigensians who joined the Order of the Temple transferred their property to it. This is particularly important because the Albigensians, who initially considered being perfecti or profane to be independent from the estate of their members, after joining the Order became particularly attentive to the difference between knights of noble origin and commoners, who at most would become surgeons and squires of the Order. The synthesis of these quite different world views solidified the subdivision of people into perfecti as people of spirit, sometimes called pneumatics, and people of matter, called profane, so that this subdivision was determined only by genetics, not by the behavior of a man or even by his personal abilities. Perfecti could be ascetics or occupy themselves with absolutely disgusting orgies, but they still remained people of spirit and humans of the higher order with respect to the profane, who were commoners and of lower estate by birth and whose right to exist was determined by their usefulness to the perfecti. The particular sign of being a perfecti was a refusal to participate in sexual procreation, which meant not the absence of physical contact with the opposite sex, but rather a refusal to create a family and give birth to children. A famous Russian movie, “The Night Guard” by Beckmambatov, almost perfectly illustrates the synthesized culture of the Templars and the Albigensians, particularly that the people of light and the people of darkness in this movie both appear to be perfecti and are in constant dynamic equilibrium with each other, while the commoners exist only as a faceless mass in the background. The group sex and other sexual perversions were considered by these descendants of the Manicheans to be a sign of being a perfecti, and the lowest level was occupied by peasants, as plants also procreate through sexual relationship, and this attitude appears to be which is in perfect harmony with the customs of the Manicheans as they were described by St. Augustine and St. Ambrosius. This cross-century philosophical continuity is both amazing and important, especially considering that these saints were among the very few apologists of Christianity who managed to convert a large number of gnostic-dualists.

Later, during the Second Crusade, the Templar knights enriched their political and religious experience by a cultural exchange with the followers of Hassan-i- Sabbah, who was the first to understand that a secret service having at its disposal fanatic murderers and terrorists, whose deadly power directed against the leaders of the enemy is much more effective than a regular army, and that sex and hashish can overcome the fear of death and supply to this secret service an unlimited amount of such fanatics. But even more important to the Templars was the discovery that the followers of Hassan-i-Sabbah were trying to achieve universal power not for its own sake, but rather as a tool, while their real goal was to create an almost scientific school of gnosis in the Castle of Alamut, which means “an Eagle’s Place.”

Meanwhile, world history was coming to a point of bifurcation that would drastically change the direction of the development of humanity. Most of the time people and civilizations develop along a certain road or a paradigm of development when one event appears to be a direct consequence of the other. This does not exclude the will of man to change the course of history and to leave this road, but it would take the enormous effort and gigantic willpower of someone like Alexander the Great or Confucius to change the flow of history just to demonstrate that the way back to the road after their death is inevitable. But sometimes humanity comes to a point of bifurcation when this road disappears and the butterfly effect becomes real, so that very small events can cause quite a substantial change in the paradigm of development, eliminating enormous civilizations while at the same time creating new ones. From that point of view it is very interesting that in 1956 a man whose name was Pierre Plantar registered a nonprofit organization under name the “Priory of Zion,” and later suggested to Europeans that they should consider reestablishing the monarchy of the Merovingians in Europe. In order to justify such a drastic political change, he identified as a point of bifurcation the year 1118, when the so-called “cutting down of an elm” took place. According to Plantar’s interpretation of history, this event caused the schism between the Priory of Zion and its military administrative instrument, the Order of the Temple, thus changing the flow of history and causing “Destruction of Europe” that we observe today. I don’t want to deny the importance of Merovingians for the unification of Western Europe, nor do I want to deny the reality of the 1000 years’ history of the Priory of Zion, however, from my point of view, the cutting down of an elm that stood on the border between Normandy and France and was a traditional place of negotiations for Norman dukes and French Kings, more than anything else meant the denunciation of the Treaty of St. Claire sur-Epte between Rollo and Charles the Simple, which made Normans the driving force of Western European civilization and for 300 years had been pulling Western Europe out of the state of barbarism and became one of the most important factors in the Christianization of Europe, including Scandinavia and Kievan Rus. Just 40 years after that the world drastically changed and the political map started to look like the one we see today.

© Alexander Brodsky

i love his blog alot, its educative. Check out the unn site by clicking http://unn.edu.ng for all your academic needs.

ReplyDelete