After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian Orthodox Church was suddenly emancipated from the external pressure of the atheistic State and spent the next twenty years enjoying unprecedented growth. But like a diver brought to the surface too quickly, during this growth it forgot about the health of its internal organs and got the "bends," and should it now have the responsibility of preserving this huge endowment without the means to manage it, its health could suffer even further. Unfortunately none of the participants suggested that the Church and museums might cooperate in the promotion of Orthodox Christian culture, including the joint organization of thematic exhibitions and the dissemination of knowledge about "theology in color". Nobody suggested that this would constitute "THE MISSION" of icons in this world and that this "MISSION" might possibly be more important than property rights. Meanwhile, acknowledging the Church's expertise in creating a new, post-Soviet history of Christian art and involving it in the presentation of related museum lectures might at least partially make up for the lack of a Christian culture curriculum that for so many years has been banned in the schools, and that when (or if) these lessons are permitted, such museum lectures on Christian art history could become the foundation of this curriculum.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian Orthodox Church was suddenly emancipated from the external pressure of the atheistic State and spent the next twenty years enjoying unprecedented growth. But like a diver brought to the surface too quickly, during this growth it forgot about the health of its internal organs and got the "bends," and should it now have the responsibility of preserving this huge endowment without the means to manage it, its health could suffer even further. Unfortunately none of the participants suggested that the Church and museums might cooperate in the promotion of Orthodox Christian culture, including the joint organization of thematic exhibitions and the dissemination of knowledge about "theology in color". Nobody suggested that this would constitute "THE MISSION" of icons in this world and that this "MISSION" might possibly be more important than property rights. Meanwhile, acknowledging the Church's expertise in creating a new, post-Soviet history of Christian art and involving it in the presentation of related museum lectures might at least partially make up for the lack of a Christian culture curriculum that for so many years has been banned in the schools, and that when (or if) these lessons are permitted, such museum lectures on Christian art history could become the foundation of this curriculum.The most balanced outlook was presented by Irina Lebedeva, director of the Tretyakov Gallery. She bravely fought against the very principle of the opposition of Church and culture, arguing that in this area the interests of the Church and museums are the same. But she began her speech with a strange, nearly incomprehensible statement: “We are people of Orthodox Christian culture. And we all grew up in its system of values. It is genetically inherent in us. Why are we suddenly so strangely contrasted? I resent the fact that passage of such a law without considering the opinion of museum experts may, paradoxically, quite without meaning to - it is clear that no one wants to harm — will suddenly finalize the struggle that was started by the Bolsheviks during the revolution and that was continued under the Soviet regime.”

By these words it seems that the director of the Tretyakov Gallery is implying that the Bolsheviks initiated the conflict of Christianity and icons as art. It is with deep regret that we must acknowledge that Irina Lebedeva is right: As a result of a bizarre set of circumstances following the Great October Socialist Revolution, Orthodox icons have actually become part of the anti-Christian, so-called "modern" culture that originated in the Renaissance and is commonly known as “secular humanism.” And the person responsible for this situation is the great Russian art historian — and Irina Lebedeva’s predecessor as director of the Tretyakov Gallery from 1913 to 1925 — Igor Emmanuilovich Grabar.

By these words it seems that the director of the Tretyakov Gallery is implying that the Bolsheviks initiated the conflict of Christianity and icons as art. It is with deep regret that we must acknowledge that Irina Lebedeva is right: As a result of a bizarre set of circumstances following the Great October Socialist Revolution, Orthodox icons have actually become part of the anti-Christian, so-called "modern" culture that originated in the Renaissance and is commonly known as “secular humanism.” And the person responsible for this situation is the great Russian art historian — and Irina Lebedeva’s predecessor as director of the Tretyakov Gallery from 1913 to 1925 — Igor Emmanuilovich Grabar.Igor Grabar was one of those intellectuals who, like Lunacharski and Timiriazev, immediately after the Great October revolution transferred his allegiance to the service of the Soviet government without any reservation. Igor Grabar participated in the work of a commission that confiscated precious objects from the Russian Orthodox Church, however, at the same time he was the one who saved Russian icons from extinction by convincing the Communist government that these icons were actually national art treasures. But in order to achieve this goal he perpetuated the lie that icons are merely pictorial phenomena having no essential connection with Christianity. Now, twenty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, this lie — like rust on metal — continues to corrupt Orthodox Christian culture from within.

In 1918 Grabar participated in the organization of the Glavmuzey of Narcompros (Museum Department of the State Department of Education). Two problems interested him at this time: the salvation of art works from vandalism and their restoration. He actively participated in the creation of the State Museum Fund, which distributed works of art to Russian museums following the nationalization of the largest art collections, including the treasures of Trinity-Sergius Lavra.

As an introductory matter it is incumbent to note that in adulthood — and without exaggeration having no financial or any other resources — I found myself a student of art history at Pratt Institute, which obviously happened under very strange circumstances due to an altered state of my mind. As a result of my training at Pratt, I came to understand why heirs to the throne of England, before they enter into service in Her Majesty’s armed forces, usually study art history. It was amazing to discover that besides the politicized history of the masses and economic formations there exists a history of men's decisions and actions, a history of their souls and inspirations, which caused them to pick up a brush and make the miracle called art. So what? Looking back, the only more or less sensible explanation to this madness is that it provided an opportunity for me to write this article on iconography as fine art. So here it is.

As an introductory matter it is incumbent to note that in adulthood — and without exaggeration having no financial or any other resources — I found myself a student of art history at Pratt Institute, which obviously happened under very strange circumstances due to an altered state of my mind. As a result of my training at Pratt, I came to understand why heirs to the throne of England, before they enter into service in Her Majesty’s armed forces, usually study art history. It was amazing to discover that besides the politicized history of the masses and economic formations there exists a history of men's decisions and actions, a history of their souls and inspirations, which caused them to pick up a brush and make the miracle called art. So what? Looking back, the only more or less sensible explanation to this madness is that it provided an opportunity for me to write this article on iconography as fine art. So here it is.The Edict of Milan did not have much of an effect on the level of religious tolerance in the Roman Empire, and a large number of pagan and dualistic sects continued to exist side by side with Christianity. For instance, on November 13, 354, in the African province of Numidia, a son was born to a family consisting of a pagan father and a Christian mother. He was named Augustine and later became famous as St. Augustine of Hippo. In his youth Augustine was interested in religious philosophy, and his outstanding intellectual abilities attracted the attention of the hierarchy of the rich and powerful dualist sect of the Manicheans. But in 383 he went to Rome and then to Milan, where he met the bishop of Milan, St. Ambrose. St. Ambrose — one of the greatest apologists of Christianity — managed to reveal to the young, brilliant Manichean the intellectual greatness of Christianity, and in 387 he received baptism at St. Ambrose’s hands. For this article, it is very important to note that both St. Augustine and St. Ambrose, being prominent Christian theologians, left writings, e.g., “On the nature of good” and “Against the Manicheans," which describe in detail the religious philosophy of the Manicheans. According to Manichean philosophy, all things were created by two contrasting creators, Good and Evil — Good being associated with Spirit and Evil with Matter. In contrast to monotheistic, Abrahamic Christianity, which according to St. Augustine explains the origin of Evil as the result of abuse by humans of the God-given free will, the Manicheans rejected the principle of free will as absurd and considered Evil to be a co-creator of the universe. In the identification of matter with evil and denial of the Abrahamic worldview, the Manichean teachings echo the anti-Judaic, anti-Abrahamic sect of Gnostic-Nicolaitans (Rev.2:6). These were followers of the heresiarch Marcion, who strongly objected to the Old Testament, claiming that it depicted a merciless demiurge that created universe "ex nihilo" or "out of nothing", and that the predicted Messiah of the Jews was the Antichrist.

Even after the Edict of Milan communities of Christians, Jews and Gnostics lived together in the tolerant cosmopolitan Christian empire, walking the same streets, praying next to each other and sometimes hiring the same artists to decorate their temples and their tombs. But gradually it became evident that the spiritual life of the community greatly influenced works of art such as the frescoes of Dura-Europos in Syria, where a Christian church (domus ecclesiae), a synagogue and a temple of Mithra stood in close proximity to each other.

The most well preserved and interesting find in Dura-Europos was a synagogue. Contrary to popular opinion about Jewish art, it was richly decorated with images of humans and animals, which suggests that the interpretation of the Fourth Commandment as a prohibition on images of animals and humans in the Jewish world was not universally accepted, to put it mildly. It is surprising that these frescoes in a third century Syrian synagogue clearly demonstrate features typically characteristic of Jewish identity, and were similar not only to the paintings of the Christian Church in Dura-Europos, but overcoming time and a distance of 4,000 kilometers, to the wall paintings found in the Christian catacombs of Rome. Amazingly, these murals are also similar to the paintings of Marc Chagall and Jewish religious articles exhibited on Grand Street on New York City's Lower East Side. The characteristic feature of this style is a conscious departure from realistic image styling and a paradoxical sense of composition, which creates a sense of presence within this world of the "other world." This paradoxical sense of composition, which can be described as "other worldliness" or maybe as symbolism, is characterized by dynamics of composition that to a large extent result from the interaction of pictorial and literary components of a given piece of art, so that literary associations of the image constitute a single entity with the pictorial composition and substantialy influence the interaction of image and viewer.

Finding Baby Moses. Finding Baby Moses.Synagogue Dura Europas. 230 A.D. |  Three women from the Crypt. (Mark 16:1)] Baptistery of Dura-Europos. 230 AD |

Consecration of the Tabernacle(Exodus 40: 17 & Numbers 7:1) Dura Europos (245 AD) |  Mithra slaying the bull. Dura Europos 230 AD |

Prophet Ezekiel. Synagogue Dura-Europos. 260 AD. |  Three youths in the fiery furnace. Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome 320 AD |

Orans (Donna Vilata), Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome, beginning fourth century. |  Orans, Catacombs Giorgione, Rome, beginning fourth century. |

Virgin and Child Jesus, Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome, early 4th c. Virgin and Child Jesus, Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome, early 4th c. |  The Good Shepherd,Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome, 4th c. AD |  Jesus, Priscilla Catacomb, 4 c. A.D. |

1. Compositional dominance of the human figure over the elements of landscape or objects;

2. Lack of interest in creating the illusion of three dimensional space. The pictorial space is governed by hierarchical perspective, so that the size of the figures of the visual field is determined by its theological significance, and not by the geometric size or location in the imaginary three-dimensional space;

3. A set of visual devices intended to make the viewer a part of the composition or to impress upon him that he is not looking at the icon, but the icon is looking at him. These devices include (but are not limited to): (i) inverse perspective; (ii) changing of the proportions of face and eyes; and (iii) using gold and precious stones as visual elements of the composition;

4. Anatomical truthfulness of the portraiture is subjected to the psychological or spiritual truthfulness, i.e., the artistic task of showing the human face as a mirror of the soul is more important than the physical characteristics of the figures. It is due to this artistic task that in Russian tradition the human face on an icon showing the soul of a Saint is called "Lik"

It is clear that the first, second and third characteristics listed above are the consequence of the theology of the incarnation of God and Christian еcclesiology. The second characteristic shown above derives from the Abrahamic, and possibly also ancient Egyptian traditions, but it was tradition of Roman sculptural portraiture that finalized the appearance of iconography. This tradition to a large extent was coming from the cult of ancestors and the tradition of patrician families to decorate their palaces with death masks of their ancestors. Indeed, Hellenistic artists lacked the skill of depicting strong emotion, and still less the spiritual life, on the human face. In order to understand the contribution of Roman portraiture it is enough to glance at the face of Lacoon's son, being strangled by a snake and compare it with the Roman portraiture-head of Plotinus.

Lacoön and His Sons, Vatican Museums, Rome, 1-st century B.C. |  Plotinus, Roman sculpture. Ostia museum, 3-rd c. A.D. |

«Hagia Sophia». Constantinople. |  Apse of Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe. Ravenna, Italy Apse of Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe. Ravenna, Italy |

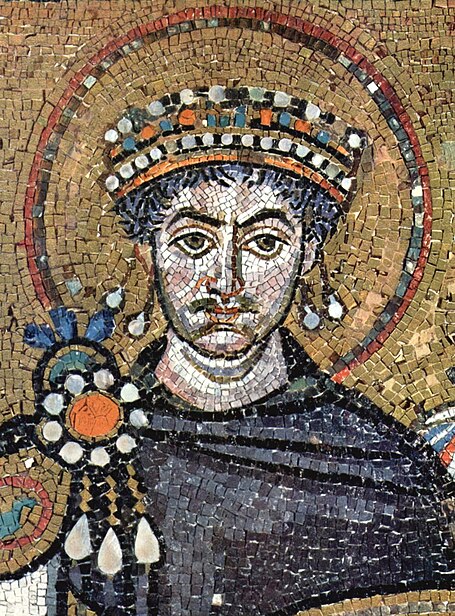

If one looks at the whole tenure of the Orthodox Christian Empire, it is difficult not to conclude that the height of its development was the construction of Hagia Sophia in 537 A.D. by Emperor Justinian. But looking back at the history of Byzantium one cannot avoid the impression that at that exact moment the amazing achievements of the emperor-genius provoked the jealousy of some esoteric community that would prove to be a consistent and strategically thinking enemy of the Christian Empire, one whose plans were not limited by the span of one human's life. While trying to understand this, the first thing that comes to mind is that Justinian, for political reasons, began his reign by closing the anti-Abrahamic philosophical schools in Athens, including the Plato Academy. The philosophers launched a grudge match in the Hippodrome, but the Green/Blue Nika came up against the iron will of a woman who had been through the hell of the theater named Pornh and the brothels of Alexandria. When the Emperor was preparing to flee Constantinople his wife stopped him and inspired furious resistance to the riots by saying:"Those who were born cannot avoid death, but for those who once were rulers, being refugees on the run is unbearable," followed by "the purple of the imperial power is the best burial shroud".

If one looks at the whole tenure of the Orthodox Christian Empire, it is difficult not to conclude that the height of its development was the construction of Hagia Sophia in 537 A.D. by Emperor Justinian. But looking back at the history of Byzantium one cannot avoid the impression that at that exact moment the amazing achievements of the emperor-genius provoked the jealousy of some esoteric community that would prove to be a consistent and strategically thinking enemy of the Christian Empire, one whose plans were not limited by the span of one human's life. While trying to understand this, the first thing that comes to mind is that Justinian, for political reasons, began his reign by closing the anti-Abrahamic philosophical schools in Athens, including the Plato Academy. The philosophers launched a grudge match in the Hippodrome, but the Green/Blue Nika came up against the iron will of a woman who had been through the hell of the theater named Pornh and the brothels of Alexandria. When the Emperor was preparing to flee Constantinople his wife stopped him and inspired furious resistance to the riots by saying:"Those who were born cannot avoid death, but for those who once were rulers, being refugees on the run is unbearable," followed by "the purple of the imperial power is the best burial shroud"."God works in mysterious ways" - "behind every great man stands a great woman!"

The husband of this woman was not only the emperor of the Byzantines but also a great theologian, so he celebrated the suppression of the sports fans' rebellion by building the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia. Justinian had come to understand that the form of the dome should be expressed by a mathematical formula, and even that mathematics should be a universal language of science, and by this understanding he became the father of the scientific method. During the construction of Hagia Sophia he appointed two professors of mathematics, Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, to supervise the work of the masons constructing the dome in order to codify their secrets into a mathematical formula available to anyone willing to learn mathematics and physics. Keeping in mind that the philosophers of Plato’s Academy considered mathematics to be the language of gods, which should be known only to the initiated, it's no surprise that the masons constructing the dome tried to hide their secrets and sabotaged the derivation of this formula, resulting in the collapse of the dome. But the traditional Imperial prosecution of this sabotage (decimation) convinced the masons to reveal their secrets to Isidore and Anthemius and the second attempt to construct the dome succeeded. The geometrical formula of the dome appeared to be an ellipse, that is, one of the conic sections and these results became the first mathematical theory on the construction of domes. Isidore and Anthemius presented their results in the apocryphal Book XV of Euclid's Elements, but these results reached us in the commentaries of Eutocius of Ascalon on the first four books of the Conics of Apollonius of Perga and on the books of Archimedes. Almost a thousand years later these books precipitated a chain of discoveries by Tiho Brahe, then Johan Keppler and finally Sir Isaac Newton, which resulted in the appearance of the modern scientific method, articulated by Sir Isaac Newton in "Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica" - the first book of modern science, whose appearance signified the beginning of the scientific revolution.

The husband of this woman was not only the emperor of the Byzantines but also a great theologian, so he celebrated the suppression of the sports fans' rebellion by building the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia. Justinian had come to understand that the form of the dome should be expressed by a mathematical formula, and even that mathematics should be a universal language of science, and by this understanding he became the father of the scientific method. During the construction of Hagia Sophia he appointed two professors of mathematics, Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, to supervise the work of the masons constructing the dome in order to codify their secrets into a mathematical formula available to anyone willing to learn mathematics and physics. Keeping in mind that the philosophers of Plato’s Academy considered mathematics to be the language of gods, which should be known only to the initiated, it's no surprise that the masons constructing the dome tried to hide their secrets and sabotaged the derivation of this formula, resulting in the collapse of the dome. But the traditional Imperial prosecution of this sabotage (decimation) convinced the masons to reveal their secrets to Isidore and Anthemius and the second attempt to construct the dome succeeded. The geometrical formula of the dome appeared to be an ellipse, that is, one of the conic sections and these results became the first mathematical theory on the construction of domes. Isidore and Anthemius presented their results in the apocryphal Book XV of Euclid's Elements, but these results reached us in the commentaries of Eutocius of Ascalon on the first four books of the Conics of Apollonius of Perga and on the books of Archimedes. Almost a thousand years later these books precipitated a chain of discoveries by Tiho Brahe, then Johan Keppler and finally Sir Isaac Newton, which resulted in the appearance of the modern scientific method, articulated by Sir Isaac Newton in "Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica" - the first book of modern science, whose appearance signified the beginning of the scientific revolution.  But it is even more important to acknowledge that Emperor Justinian became the greatest iconographer of all times by bringing Hagia Sophia to reality. In doing so he surpassed even King Solomon by creating in this world the most perfect image of the synergy of human will and the will of God, which appeared in his imagination as an icon of the whole creation saved by the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. Even the laws of nature, providentially opened to the human intellect by the Grace of God, as well as human history itself, seem to constitute the paints of his palate. Indeed it was the heavenly beauty of Hagia Sophia that so impressed Grand Prince of Kiev, Vladimir the Red Sun that he proceeded to baptize all of Kievan Rus, thus creating the heir to the Orthodox Christian Empire, Holy Rus, which after the collapse of Byzantium became the Third Rome. Science, including the idea of mathematics as a universal scientific language, was invented by Justinian while trying to "draw in his mind" the icon of Hagia Sophia. But his understanding of science was as "the humility of wisdom" rather than as an interrogation of nature, as science was later described by Galileo Galilei. In the process of designing Hagia Sophia Justinian revealed to humanity the meaning of the commandment to Man to be the gardener of the universe: by finding out the real – not fallen – names of the laws of nature, described in scripture as fallen stars, he could gain power over them, and thus return them to the domain of the King of Heaven, whose name is Love. Thus Justinian completed the process of building the archetype of liturgical art, making the house of God not only a place for liturgy where icons are venerated, but making the whole building an icon and its construction a symbol of Genesis and the "beauty of Christ, which will save the world."

But it is even more important to acknowledge that Emperor Justinian became the greatest iconographer of all times by bringing Hagia Sophia to reality. In doing so he surpassed even King Solomon by creating in this world the most perfect image of the synergy of human will and the will of God, which appeared in his imagination as an icon of the whole creation saved by the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. Even the laws of nature, providentially opened to the human intellect by the Grace of God, as well as human history itself, seem to constitute the paints of his palate. Indeed it was the heavenly beauty of Hagia Sophia that so impressed Grand Prince of Kiev, Vladimir the Red Sun that he proceeded to baptize all of Kievan Rus, thus creating the heir to the Orthodox Christian Empire, Holy Rus, which after the collapse of Byzantium became the Third Rome. Science, including the idea of mathematics as a universal scientific language, was invented by Justinian while trying to "draw in his mind" the icon of Hagia Sophia. But his understanding of science was as "the humility of wisdom" rather than as an interrogation of nature, as science was later described by Galileo Galilei. In the process of designing Hagia Sophia Justinian revealed to humanity the meaning of the commandment to Man to be the gardener of the universe: by finding out the real – not fallen – names of the laws of nature, described in scripture as fallen stars, he could gain power over them, and thus return them to the domain of the King of Heaven, whose name is Love. Thus Justinian completed the process of building the archetype of liturgical art, making the house of God not only a place for liturgy where icons are venerated, but making the whole building an icon and its construction a symbol of Genesis and the "beauty of Christ, which will save the world."Orthodox Christianity paid dearly while fighting with heresies to arrive at the understanding that the Church cannot and should not have secret knowledge, that the way to salvation is not through gnosis but through faith. And faith requires that a man must have the possibility of knowing all the teachings of the Church even before receiving baptism, so that he may join the Church knowing what Christianity is. So it is no accident that Emperor Justinian, being an Orthodox Christian theologian, understood that the laws of nature also should not be a secret but available to everybody willing to learn them. This understanding derived during the discovery of the geometrical formula of the dome of Hagia Sophia was probably the heaviest blow to gnosticism, as it made knowledge not a mystery known only to the initiated, but the objective truth available potentially to everyone. So it is no surprise that less than fifty years later the Orthodox Christian Empire was forced to face a new problem, which factored not only in the destruction of Byzantium but also in the more recent destruction of the U.S.S.R. That problem appeared under very mysterious circumstances, but the similarity of historical circumstances connected with the crisis of Justinian’s Byzantium and the Soviet Union is even more amazing. Indeed at the moment of its greatest achievements, almost 1500 years before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Orthodox Christian Empire not only found itself at war with a younger Abrahamic religion, but it also became the object of a networked information warfare surrounding questions of iconography and implementing the principle of resonance, when the extremities of one group was inflaming the extremities of the other. To being with, the fire of the arguments about the heresy of Eutyches (monophysite), which already had been solved in the Church and was suppressed in the Empire by the joint efforts of St. Theodora and St. Justinian, suddenly flared up again. This fire became even more furious when different questions raised by this controversy, which had not yet been considered by the Church, suddenly became associated with the national/ethnic factor. Diophysitism appeared to be the point of view of "intelligent, sophisticated Hellenes" while miaphysitism became the destiny of "Coptic and Armenian vulgar barbarians." It is obvious that such a justification did not help to solve these theological problems, nor did they contribute to peace in the multinational empire. It became especially ugly when another argument – between iconoclasts and icon-worshipers – began and progressed across the same ethnic lines. And to make things worse, while this was all happening, an Islamic invasion began.

When one considers these circumstances, the first question that presents itself is what is the root of the heresy of iconclasm? Once we discover that iconography itself comes from the Abrahamic artistic tradition, the usual explanation – that iconoclasm was a literal interpretation of the Fourth Commandment – cannot be considered satisfactory. Fifteen hundred years ago, when atheism was only a nuisance, such a manipulation of public opinion and contradiction with everyday reality was not likely to find a vast amount of followers, especially if one considers that a religion that forbade images of humans and animals was right in front of their eyes, preparing to storm their gates. This is especially difficult to believe if one remembers that in 718 A.D. Leo III the Isaurian had just celebrated the "Russian winter" of 717, not a summit with Caliph Suleiman at a summit in Reykjavic. Why would he imitate a defeated enemy? Meanwhile, if one analyzes the protocols of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, he will conclude that iconoclasm was coming in the same package with icon-worship, a practice where people used paint from icons as medicine, believed that it could heal from any disease and even were putting it into the chalice during the liturgy. The iconoclasts said that if such a heresy as icon-worship was in practice, the only way to object to it was to take the Islamic point of view. There was no serious discussion of this question in the Church before the bloodshed started. Meanwhile, as later history showed, this question was of extreme importance. This question was a focal point of different paradoxes of Christianity in which all of the previous achievements of Orthodox theology took substance, becoming material.

When one considers these circumstances, the first question that presents itself is what is the root of the heresy of iconclasm? Once we discover that iconography itself comes from the Abrahamic artistic tradition, the usual explanation – that iconoclasm was a literal interpretation of the Fourth Commandment – cannot be considered satisfactory. Fifteen hundred years ago, when atheism was only a nuisance, such a manipulation of public opinion and contradiction with everyday reality was not likely to find a vast amount of followers, especially if one considers that a religion that forbade images of humans and animals was right in front of their eyes, preparing to storm their gates. This is especially difficult to believe if one remembers that in 718 A.D. Leo III the Isaurian had just celebrated the "Russian winter" of 717, not a summit with Caliph Suleiman at a summit in Reykjavic. Why would he imitate a defeated enemy? Meanwhile, if one analyzes the protocols of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, he will conclude that iconoclasm was coming in the same package with icon-worship, a practice where people used paint from icons as medicine, believed that it could heal from any disease and even were putting it into the chalice during the liturgy. The iconoclasts said that if such a heresy as icon-worship was in practice, the only way to object to it was to take the Islamic point of view. There was no serious discussion of this question in the Church before the bloodshed started. Meanwhile, as later history showed, this question was of extreme importance. This question was a focal point of different paradoxes of Christianity in which all of the previous achievements of Orthodox theology took substance, becoming material. To consider the entire history of iconoclasm in Byzantium is absolutely impossible in such a short article as this one, but it is absolutely mandatory to mention that this was the first time that the Empire acted as if the Church was a department of the imperial office. Without discussing this question inside the Church, the government began to solve the question by force. Besides, from the very beginning, the manner in which the problem was formulated was most extreme – what is better, iconoclasm or icon-worship? It is obvious that there is no right answer to a wrong question, and the Church at the Seventh Ecumenical Council gave the only possible answer: both are worse. In the same manner for modern Russia, the discussion of a new law about transferring property to the Church raised some questions in the most extreme manner possible, for instance: "what is an icon – a piece of art, or a cult object?" It is apparent that this question is really a question to be considered by the Church, but the way it is formulated shows that, as it was 1200 years ago in Byzantium, it is again articulated not by the Church but was brought into Church discussion by forces external to the Church. The present day situation is absolutely the same as in the time of Justinian – anti-Christian minds analyzing the life of the Church and, finding the most crucial problem ignored by the hierarchy, articulating it instead of them, so that now, when this problem is discussed it becomes impossible to solve it on Christian terms. Thus becoming a situation that could cause the Church to schism. Meanwhile, this problem is a real one and first of all requires significant intellectual effort to articulate the question. In order to do this the cooperation of the hierarchy, iconographers, art historians and museum workers is absolutely necessary, especially considering that many museum workers are also members of the Church. No matter what, the icons are a national treasure and it is apparent that today in Russia the last word in this argument will be pronounced by the State and that it will take into account the interests of all people of Russia, even those who are not Christian. That's why the hierarchy needs the support of each and every Orthodox Christian citizen of Russia, especially museum workers, and clearly a consolidated "sobornoe" articulation of this problem is absolutely necessary.

© Alexander Brodsky

No comments:

Post a Comment